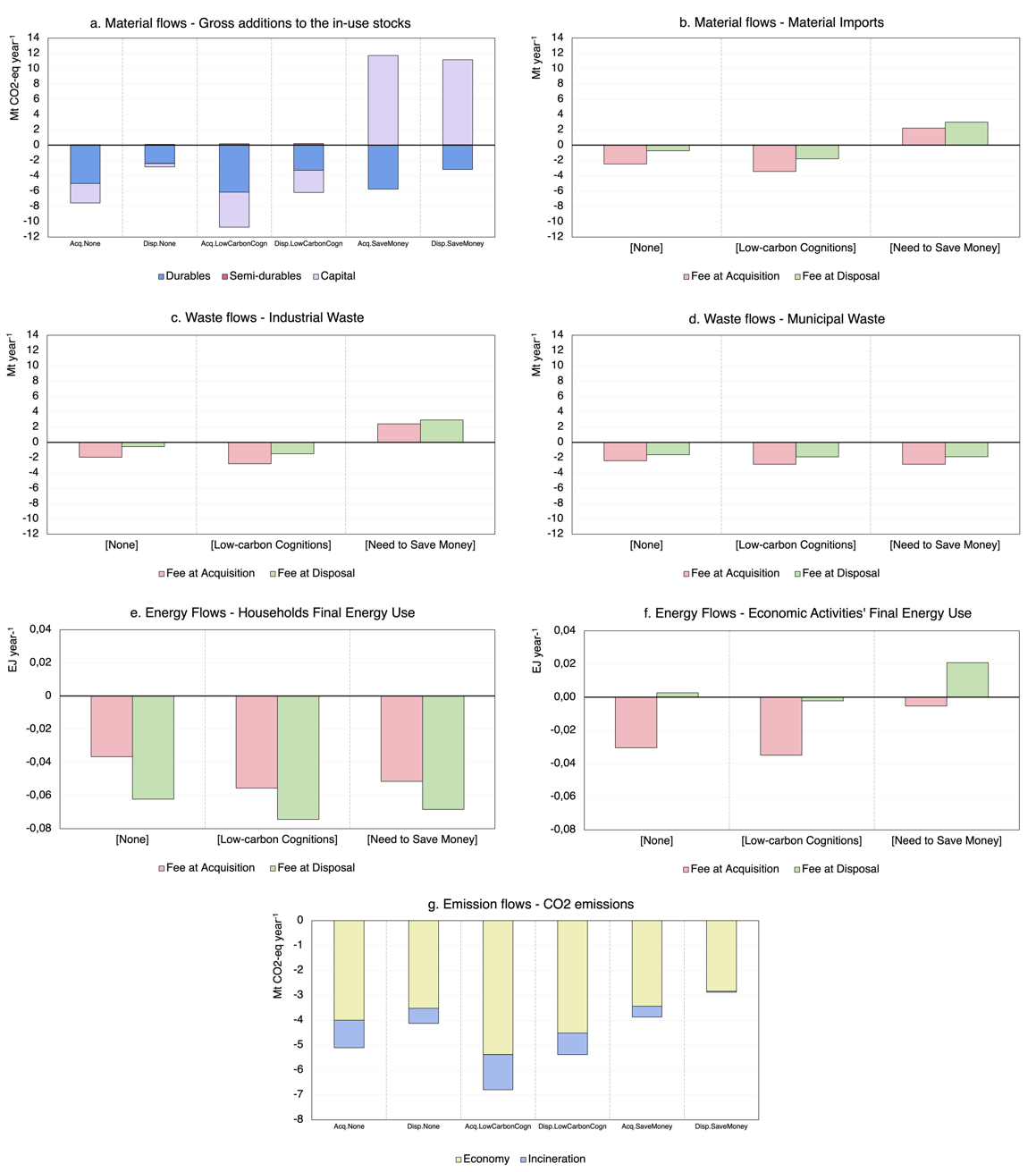

Figure 1: Graph a. shows the deviation of gross additions to the in-use stocks of semi-durable goods, durable goods and capital goods from current policy scenario by 2050 in Million tonnes. Graph b. shows the deviation of total material imports from current policy scenario by 2050 in Million tonnes per year. Graphs c. and d. show the deviation of industrial and municipal waste from current policy scenario by 2050 in Million tonnes per year. Graph e. and f. show the deviation of households’ and economic activities’ final energy use from current policy scenario by 2050 in EJ per year. Graph g. shows the deviation of CO2 emissions for the economy but the incineration sector (yellow) and incineration sector (purple) from current policy scenario by 2050 in MtCO2 per year. Graph a. and Graph f. axis legends read as follows : ’Acq.’ corresponds to a fee imposed at the point of acquisition, ’Disp.’ corresponds to a fee imposed at the point of disposal, ’.None’ corresponds to no sufficiency behavior drivers, ’.LowCarbonCogn’ corresponds to sufficiency behavior driven by low-carbon cognitions and ’.SaveMoney’ corresponds to sufficiency behavior driven by the need to save money. Source: CIRCEE-LIFE simulations

Japan’s efforts to transition to a circular economy have been shaped by decades of challenges – ranging from limited landfill capacity and environmental issues to the need to reduce resource consumption for enhanced economic security. Although the Basic Act for Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society has reduced municipal waste and increased the recycling of specific waste streams, Japan remains highly dependent on primary resource imports and still generates a significant amount of waste. Our recent study (Corbier et al., 2025*) explores how Japan’s Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes can be strengthened through consumer lifestyle changes. Focusing on energy-using durable goods, we assess how increasing EPR fees could alter consumption habits and boost “consumer” circular economy practices with the CIRCEE-LIFE model (Corbier et al., 2024**).

Key Insights

- Policy timing matters: The results reveal that charging the EPR fee at the time of purchase rather than at disposal immediately affects households’ consumption behaviors and more effectively reduce new product purchases. This shift not only encourages repairs and sharing services but also contributes to lower waste generation (refer to Fig. 1 below).

- Lifestyle changes are antecedent to EPR schemes: We distinguish two scenarios in which sufficiency behaviors are either driven by low-carbon cognitions or by the need to save money. When sufficiency behaviors are driven by low-carbon cognitions, there is a higher response to EPR fees and higher engagement in repairs and sharing services. When sufficiency behaviors are driven by the need to save money, the impact of weak intentions towards sufficiency in the consumption of energy-using goods is stronger than the price effect from EPR fees.

- Environmental trade-offs: While higher EPR fees result in lower CO2 emissions by curbing waste and resource use (refer to Fig. 1 below), they may also lead to rebound effects by promoting the use of less-energy efficient repaired goods and encouraging the substitution toward more resource-intensive consumption goods.

Policy Implications

This work highlights the importance of aligning consumer behavior and producer responsibility to encourage circular-related consumption practices – not only in Japan but as a model for other regions, such as the EU, facing similar resource and waste management challenges. Tailoring circular economy strategies to support diverse consumer segments – particularly those motivated by environmental values – can enhance the positive impacts of EPR schemes.

When fees are “visible” at the time of purchase, consumers are more likely to internalize the environmental cost, shifting their preference toward repair and sharing services. This can effectively reduce resource demand and waste generation, although attention must be paid to potential rebound effects. To mitigate these rebound effects, policies should pair repair incentives with measures to improve energy efficiency of repaired goods.

By Darius Corbier – RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment

* Corbier, D., Pettifor, H., Agnew, M., Nagashima, M. (2025). Shaping sustainable consumption practices: changing consumers’ habits through lifestyle changes and Extended Producer Responsibility schemes. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 217 (108214).

** Corbier, D., Pettifor, H., Agnew, M., & Drouet, L. (2024). CIRCEE, the CIRCular Energy Economy model: Bridging the gap between economic and industrial ecology concepts. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 28(06), 1996-2011.